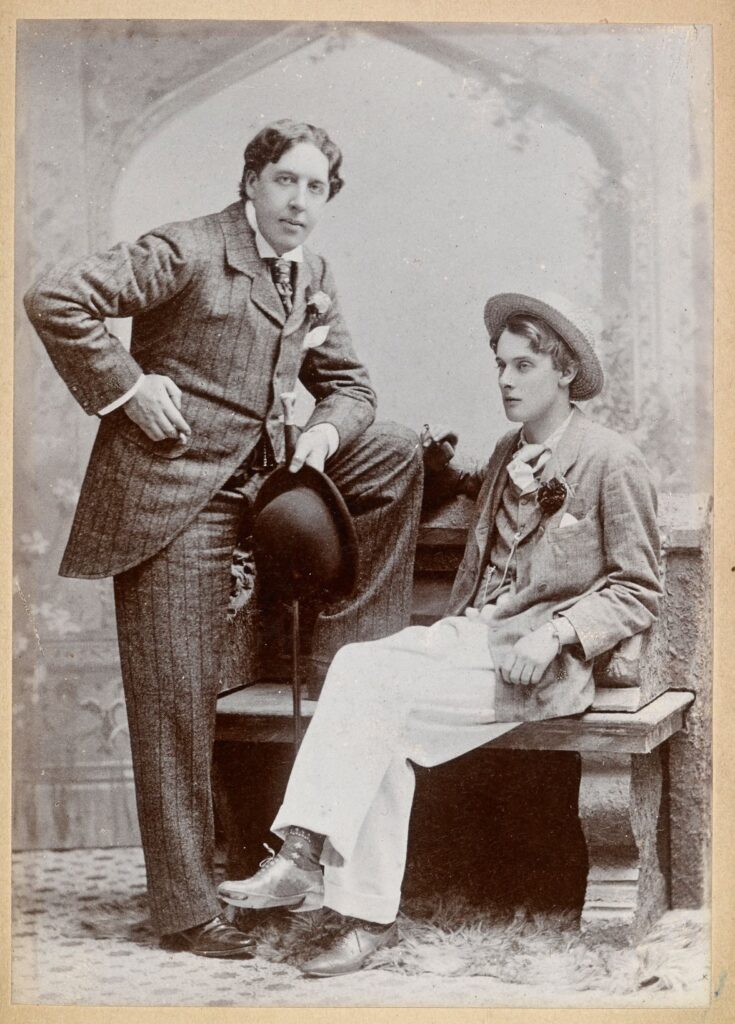

”The love that dare not speak its name”

With those words playwright Oscar Wilde described his relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas in the legendary trial held in London in 1895. Once forbidden, love between men was addressed more or less openly in literature as early as the beginning of 20th century. Now, the Finnish National Ballet has received a version of one of the masterpieces, Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice, interpreted by choreographer John Neumeier as a ballet.

Wilde’s characterization of his own love is apt, as during the time of the trial, homosexuality indeed did not have a proper name, but only very derogatory terms in various languages. In 1869, Hungarian Karoly Maria Benkert coined the terms ”heterosexual” and ”homosexual,” which were free from value judgments, but they did not come into wider use until the early 20th century.

The real revolution was the Kinsey Report, published in the United States in 1948, based on interviews with thousands of men revealing the spectrum of their sexual identities. It was followed by a similar study on women’s sexuality. The reports paved the way for the sexual revolution of the 1960s and the relaxation of laws criminalizing homosexuality, which in Finland began in 1971.

In practice, gay men were thus outlaws in almost all of Europe during the 19th century and early 20th century, except in France, whose 1810 law allowed relations between men. This is why Oscar Wilde, after serving his sentence in a penal colony, retreated to die to France, where a large number of upper-class Englishmen had already moved to escape the broader implications of Wilde’s trial. England’s law had just been amended so that one could be charged based on mere denunciation, which is why it was called the blackmailer’s charter.

Thomas Mann and his contemporaries

Thomas Mann had addressed homosexuality in his books based on his own experiences, and his diaries also contained sensitive information about his life. Mann fled the rise of National Socialism from Munich to Switzerland in 1933 and left his diaries hidden at home. One can understand Mann’s deep anxiety as he awaited the delivery of his diaries from the Nazis to safety in Switzerland. The persecutions of homosexuals initiated by the Nazis led to the imprisonment and deportation to concentration camps of tens of thousands of men – relationships between women were not criminalized.

Similar feelings of fear and anxiety were shared by many of Mann’s contemporary writers. One of them was the American-British Henry James, who in many of his novels depicts the encounters between American and European attitudes. He kept his sexual orientation strictly secret. However, later revealed correspondence shows deep feelings towards young men. James’s estate did everything to conceal the letters, so they were only made public half a century after the writer’s death.

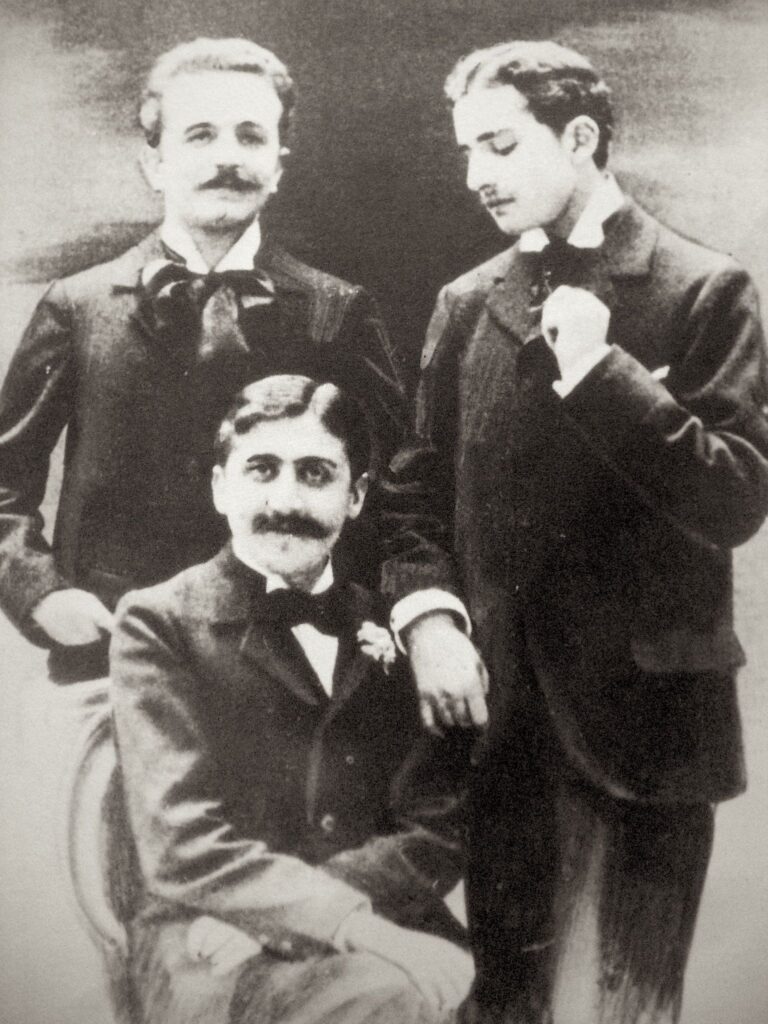

In the more liberal climate of France, Marcel Proust lived more openly. He had relationships and romances and was a familiar figure in Parisian clubs and other amusements. Nevertheless, he challenged a journalist who dared to hint at this ”secret”, which was already known to almost everyone, to a duel. In his magnum opus, In Search of Lost Time, Proust used a lot of material from his own life and that of his acquaintances, but obscured the characters’ identities, for example, by changing their gender. Similarly, in France, Nobel laureate André Gide dealt relatively openly with his sexuality in his novels. He also wrote an essay collection on the history of homosexuality, Corydon, whose publication he allowed only years later.

The English writer E.M. Forster is best known for his novel, set in colonial India, A Passage to India, which for the first time addresses the encounter between different cultures. He lived in his relationships quite openly and in 1953 publicly defended the rights of homosexuals in England. However, he allowed the publication of his central novel Maurice and his short stories dealing with homosexual themes only after his death in the 1970s. Maurice is one of the first novels about a love affairs between men to end happily, and it also transcends social class boundaries.

Thomas Mann, who hinted at his diverse sexuality in his books, allowed his secret diaries to be opened twenty years after his death, but they were only published uncensored in the early 1990s. What followed? The earth did not shake; instead, a lively Mann renaissance began. Three massive biographies were published in English alone, revealing aspects of the writer’s life, emotions, and creative processes. In Germany, a television series about the Mann family was also made. The ballet by John Neumeier based on Mann’s novella Death in Venice premiered at the Hamburg Ballet in 2003 and is now part of the National Ballet’s autumn program.

Text JUKKA O. MIETTINEN

Translation Matilda Gronow (with CoPilot)

The writer is a dance critic and non-fiction author with a doctorate in dance arts.

The head image of the article is from John Neumeier’s ballet Death in Venice. Photo Kiran West / Hamburg Ballet

Death in Venice, based in Thomas Mann’s famous novella, is part of the National Ballet’s program from November 1st to November 23rd 2024. Read more about Thomas Mann’s life and the creation of the novella from the program booklet.

Recommended for you

Javier Torres's new, stronger Giselle

Giselle’s costumes inspired by old Italian photographs

Édith Piaf – La vie en rose: Behind the Scenes with the Creative Team

Behind the scenes: Blushing

Death in Venice: insights from the choreographer and dancers

Thomas Mann and the anatomy of longing

A beginner’s guide to ballet